Images of Emotion vs. Emotion Words: A study using Galileo

The purpose of this study was

to examine the differences, if any, in the way people perceived emotion words and

pictures of people displaying those emotions. The six emotion concepts used by

this study are those that have become accepted as basic emotions by most

researchers in the last thirty years, namely, happiness, sadness, surprise,

fear, anger and disgust (Ekman & Friesen, 2003).

354 undergraduate students [excel sheet to download with slight corrections discovered summer06] in all

three sections of COM101 answered one of four possible Galileo surveys.

The word survey asked participants to compare 21 pairs of emotion words (the

six emotion concepts + "yourself") and the image survey asked

participants to compare 21 pairs of images showing facial expressions of

emotion (as posed by Dr. Mark Frank). Also, half the surveys used an alternate

criterion pair (“anger and sad are 100 units apart,” rather than “happy and sad

are 100 units apart”).

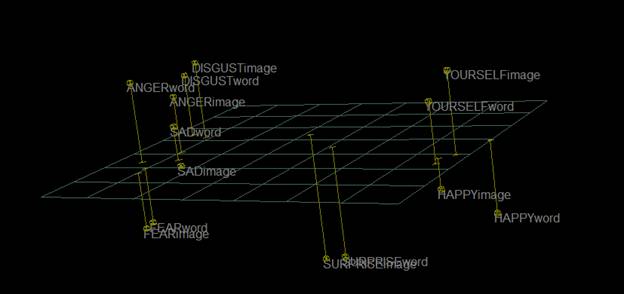

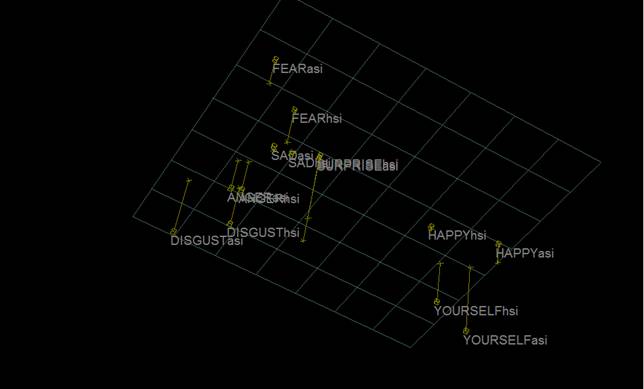

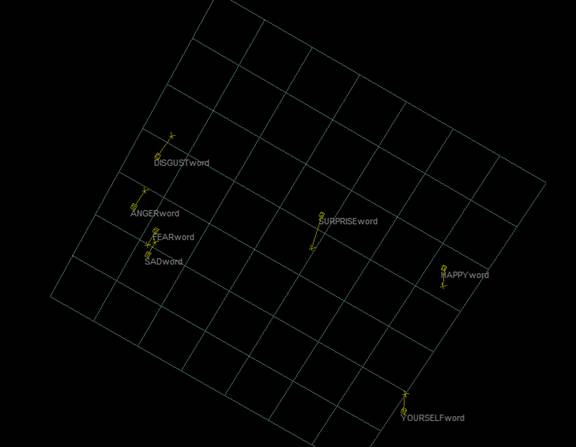

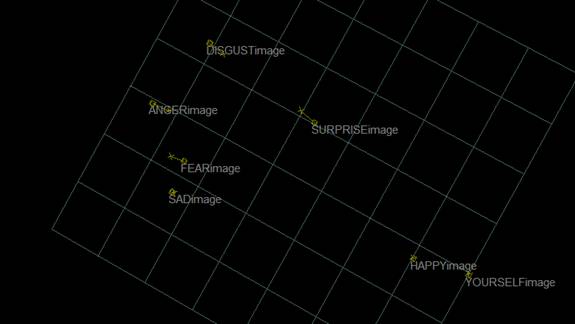

As shown in the image below, overall the word/image findings were similar.

Both the word and image surveys using the happy/sad criterion pair, shown below in two separate views,

followed the same pattern (sad, fear, anger, disgust). It should be noted, however, that sad & fear were

close on the word survey (see summary images at end).

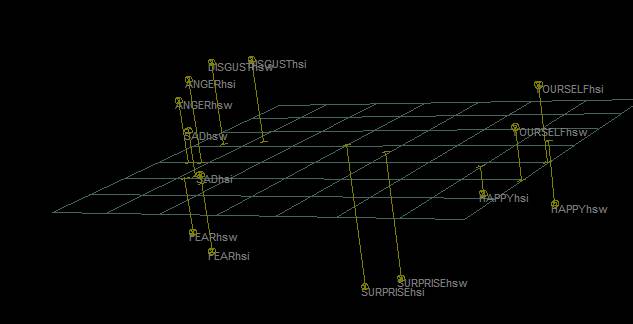

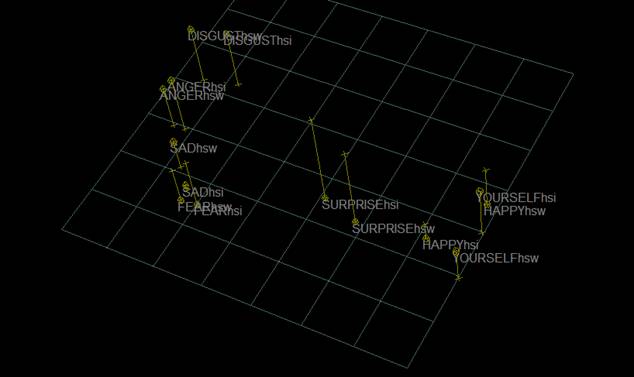

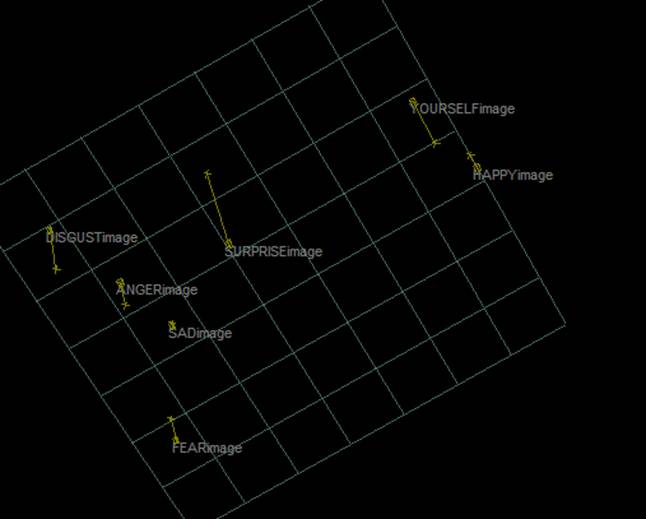

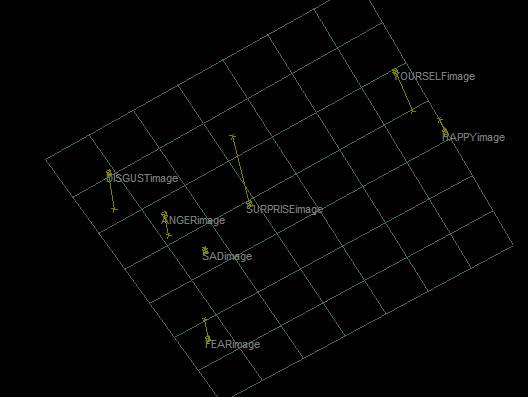

The surveys using the anger/sad criterion pair, however, came out slightly different. Basically anger,

sad, and fear moved a bit.

The image concept placement changed to fear, sad, anger, disgust…

and the word concept placement changed to fear, anger, sad, disgust. This is perhaps clearer

when the anger/sad results are viewed alone.

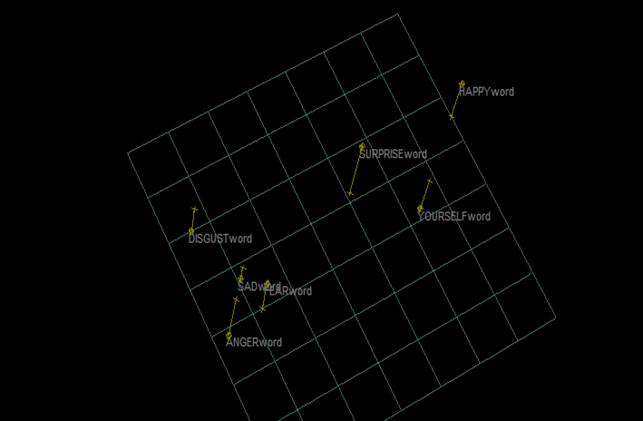

(word placement using anger/sad pair)

(image placement using anger/sad pair)

So it appears that for some reason the anger/sad criterion pair surveys have yielded slightly different results.

Since the expected placement of the emotions (based on previous work in this area) usually seems to be

sad, fear, anger (Woelfel & Fink 1980, Plutchik 1962), it appears that the close pair words may have

somehow interfered with participants’ ability to judge concept relations. It also appears to have altered the

image results more than the word results. This raises yet another possibility as the previous studies used word

pairs. It is possible that the images were regarded differently--although this possibility is considered somewhat

less likely than it otherwise might be since the happy/sad criterion pair image survey yielded results similar to the

happy/sad word surveys. Nonetheless, the possibility that this difference was possibly in part due to the use of

images should not entirely discounted since Gordon’s work on criterion pairs indicates that an opposite pair

will yield results similar to no example pair (Gordon 1976).

It should be noted that the anger/sad surveys, especially the word surveys, exhibited more unusual responses

than the happy/sad surveys. Among the most memorable were the word pudding, the square root of 25, and

pie. These surveys also exhibited more answer changes and doodles.

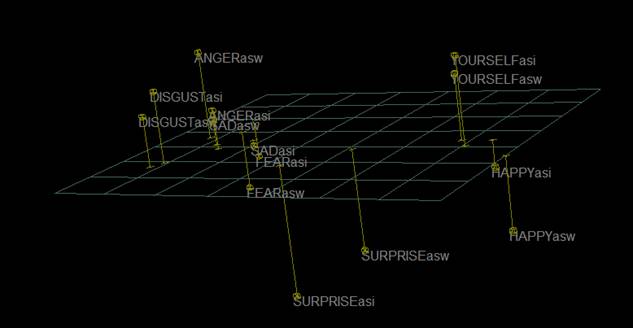

So although the close pair appears to have helped spread/differentiate the images better than (although in the

same manner as) the opposite pair, it seems it may have been more difficult to grasp the idea of assigning

values both above and below the criterion pair. While the facial images prompted that somehow…the words

did not.

Future studies using different concepts are needed to further explore how different criterion pairs may or may

not influence survey results.

**To experience a Galileo survey

first hand, feel free to visit The

Galileo Matrix website—

where a number of surveys are

continually being conducted.

[note 3-19-11: the galileo matrix link has been removed as that website no longer exists; the word happy-sad survey, however, is available at http://www.galileoco.com/surveyPortal/surveysNow.asp ]

A few last

graphics/Summary of results:

angerSad image results

angerSad word results

happySad word results

happySad image results

Partial Literature Review

The

idea of relating verbal communication (whether spoken or written) and nonverbal

communication is not new. The purpose of this study is to examine the

differences, if any, in the way people perceive emotion words (e.g., happy,

sad, etc.) and pictures of people displaying those emotions.

Darwin

in the late 1800’s was the first to systematically study facial expressions (Frank,

2003). He

proposed that emotions were displayed in the same manner by people in all

cultures (Darwin,

1898). Much

of the research after

Paul

Ekman, who resurrected Darwin’s idea of universality by proposing a theory

regarding cultural display rules (to explain why it sometimes appeared that

people in different cultures showed the same emotion differently) (Ekman,

1999b; Harper et al., 1978), indicates that there

are more words for emotions than there are emotions (Ekman,

1999a).

Further, he notes that words are but representations of emotions, not the

emotions themselves (Ekman,

2004).

This

fits well with communication semiotic theory which states, among other things, that

images represent things--yet also acknowledges that (for example) photographs

refer to, yet are not equated with, the reality they depict (Littlejohn,

1999; Noth, 1990). Verbal

signs (words), however, are not similar to what they represent in the same

manner as a photograph (Ellis,

1992).

Perhaps this is one reason that Russell was quite concerned with the format

used in many studies of emotion (Russell,

1993). He

felt that sometimes people would arrive at incorrect answers when only provided

with a small list of emotion words in response to a picture.

The six

emotion concepts used by this study are those that have become accepted as

basic emotions by most researchers in the last thirty years, namely, happiness,

sadness, surprise, fear, anger and disgust (Ekman

& Friesen, 2003). While

Ekman does acknowledge in his most recent book that the term happiness is

problematic because of its lack of specificity, he notes nonetheless that most

emotion research has concentrated on upsetting emotions rather than enjoyable

emotions (Ekman,

2004).

He goes

on to propose that the expression of enjoyable emotions may be differentiated

from one another not so much by facial affect as by the timing of the facial

expression and/or tone of voice (Ekman,

2004). As

that sort of thing would clearly be beyond the scope of this present study, the

generally accepted six basic Ekman emotions were chosen. These six emotion

words have also been used in at least two similar studies comparing facial

expressions and emotion words (although it should be noted that Brandt &

Barnett actually used 7 concepts, these six plus interest-excitement) (Brandt

& Barnett; Russell & Widen, 2002).

Since

the late 1980’s a debate has been going on as to whether pictures may be more

directly accessed by semantic memory than words. Some studies on this topic

indicated that word categorizing was slower (Glaser

& Glaser, 1989) while

others contended that there was no significant difference between picture/word

stimuli (Theios

& Amrhein, 1989). More

recent studies continue to maintain that pictures do have privileged access to

semantic memory for categories (Seifert,

1997), yet

the most recent studies continue to call that into question (R.

Adolphs et al., 2000; Amrhein et al., 2002). While most of these

studies have been concerned with the speed with which various pictorial or word

tasks are performed, they are relevant to the present study in that they have

generated various ideas on cognitive processes—some of which relate to

neuroimaging techniques and studies.

Most

studies have suggested that the left hemisphere of the brain is associated with

language and the right hemisphere with pictures (Kim et al., 2004; Vandenberghe et al., 1996). Other studies grant

that and also suggest the right hemisphere is involved with the recognition of

emotion (R.

Adolphs et al., 2000; Buck, 1999; Nakamura

et al., 1999).

Various patient studies also bear this out indicating that those with damage to

the right hemisphere perform less accurate posed expressions of emotion (Canino et al., 1999), those with lesions in

the right hemisphere have concept retrieval problems, and those with lesions in

the left hemisphere have name retrieval problems (Damasio et al., 2004).

The

most recent studies appear to bear out Farah’s contention that pictorial and textual

comprehension processes do converge on a common system of knowledge

representation at some point (Farah,

1989). As

Damasio explains, it is not so much that the traditional account is wrong as that

it is incomplete (Damasio

et al., 2004). He suggests

there is not one single system supporting word retrieval but several. This

thought is also echoed by Posner who feels recent studies in regards to

cognitive tasks suggest a network of operations (Posner,

2004). This

concept is especially important in relation to image processing and seems to

agree with findings in patient studies (Ralph

Adolphs et al., 2003; Rich et al., 2002).

Finally,

thinking about emotional concepts is also at least partly influenced by one’s

own mood and experience (Dietrich et al., 2000; Niedenthaland et al., 1997; Pollak et al., 2000).

References

Adolphs, R., Damasio, H., Tranel, D., Cooper, G., & Damasio, A. R. (2000). A role for somatosensory cortices in the visual recognition of emotion as revealed by three-dimensional lesion mapping. J Neurosci, 20(7), 2683-2690.

Adolphs, R., Tranel, D., & Damasio, A. R. (2003). Dissociable neural systems for recognizing emotions. Brain and Cognition, 52(1), 61-69.

Amrhein, P. C., McDaniel, M., & Waddill, P. (2002). Revisiting the picture-superiority effect in symbolic comparisons: Do pictures provide privileged access? Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 28(5), 843-857.

Brandt, D., & Barnett, G. Coding of facial and verbal expressions of emotion: A metric multi-dimensional scaling analysis.

Buck, R. (1999). The biological affects: A typology. Psychological Review, 106(2), 301-336.

Canino, E., Borod, J. C., Madigan, N., Tabert, M. H., & Schmidt, J. (1999). Development of procedures for rating posed emotional expressions across facial, prosodic, and lexical channels. Perceptual and Motor Skills Vol 89(1) Aug 1999, 57-71.

Damasio, H., Tranel, D., Grabowski, T., Adolphs, R., & Damasio, A. (2004). Neural systems behind word and concept retrieval. Cognition, 92(1-2), 179-229.

Darwin. (1898). The expression of the emotions in man and animals.

Dietrich, D. E., Emrich, H. M., Waller, C., Wieringa, B. M., Johannes, S., & Munte, T. F. (2000). Emotion/cognition-coupling in word recognition memory of depressive patients: An event-related potential study. Psychiatry Research, 96(1), 15-29.

Ekman, P. (1999a). Basic emotions. In T. Dalgleish & M. Power (Eds.).

Ekman, P. (1999b). Facial expression. In T. Dalgleish & M. Power (Eds.), Handbook of cognition and emotion. New York: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

Ekman, P. (2004). Emotions revealed: Recognizing faces and feelings to improve communication and emotional life. New York: Owl Books, Henry Holt and Company, LLC.

Ekman, P., & Friesen, W. (2003). Unmasking the face: A guide to emotions from facial clues. Cambridge, MA: Malor Books.

Ellis, D. (1992). From language to communication. Hillsdale, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers.

Farah, M. (1989). Knowledge from text and pictures: A neuropsychological perspective. In H. Mandl & J. Levin (Eds.), Knowledge acquisition from text and pictures (pp. 329). New York: North-Hollan.

Frank, M. (2003). Getting to know your patient: How facial expression can help reveal true emotion. In M. Katsikitis (Ed.), The clinical application of facial measurement: Methods and meaning (pp. 255-283). Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Glaser, W. R., & Glaser, M. O. (1989). Context effects in stroop-like word and picture processing. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 118(1), 13-42.

Gordon, T. (1976). Subject abilities to use metric mds: Effects of varying the criterion pair.

Harper, R., Wiens, A., & Mattarazzo, J. (1978). Nonverbal communication: The state of the art. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Kim, K. H., Yoon, H. W., & Park, H. W. (2004). Spatiotemporal brain activation pattern during word/picture perception by native koreans. Neuroreport: For Rapid Communication of Neuroscience Research, 15(7), 1099-1103.

Littlejohn, S. (1999). Theories of human communication (sixth ed.). New York: Wadsworth Publishing Company.

Nakamura, K., Kawashima, R., Ito, K., Sugiura, M., Kato, T., Nakamura, A., et al. (1999). Activation of the right inferior frontal cortex during assessment of facial emotion. J Neurophysiol, 82(3), 1610-1614.

Niedenthaland, P., Halberstadt, J., & Setterlund, M. (1997). Being happy and seeing "happy": Emotional state mediates visual word recognition. Cognition and Emotion, 11(4), 403-432.

Noth, w. (1990). Handbook of semiotics. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Plutchik, R., (1962). The Emotion: Facts, Theories, and a New Model. New York: Random House, Inc.

Pollak, S. D., Cicchetti, D., Hornung, K., & Reed, A. (2000). Recognizing emotion in faces: Developmental effects of child abuse and neglect. Dev Psychol, 36(5), 679-688.

Posner, M. (2004). The achievement of brain imaging: Past and future. In N. Kanwisher & J. Duncan (Eds.), Functional neuroimaging of visual cognition (pp. 554). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Rich, J. B., Park, N. W., Dopkins, S., & Brandt, J. (2002). What do alzheimer's disease patients know about animals? It depends on task structure and presentation format. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 8(1), 83-94.

Russell, J. A. (1993). Forced-choice response format in the study of facial expression. Motivation and Emotion, 17(1), 41-51.

Russell, J. A., & Widen, S. C. (2002). Words versus faces in evoking preschool children's knowledge of the causes of emotions. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 26(2), 97-103.

Seifert, L. S. (1997). Activating representations in permanent memory: Different benefits for pictures and words. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 23(5), 1106-1121.

Theios, J., & Amrhein, P. C. (1989). Theoretical analysis of the cognitive processing of lexical and pictorial stimuli: Reading, naming, and visual and conceptual comparisons. Psychological Review, 96(1), 5-24.

Woelfel, J., & Fink, E. (1980). The Measurement of Communication Processes: Galileo Theory and Method. New York: Academic Press

Vandenberghe, R., Price, C., Wise, R., Josephs, O., & Frackowiak, R. (1996). Functional anatomy of a common semantic system for words and pictures. Nature Vol 383(6597) Sep 1996, 254-256.